A freight pilot friend once astutely observed, "From the right seat, it may as well be a completely different airplane." His comment sprang from a discussion we had about the wisdom of non-instructor pilots offering to fly with student pilots, allowing the student to sit in the left seat and practice. The pilot would act as PIC, the cost of the flight would be shared, and there would be no need to pay for a flight instructor. When examining the relative wisdom of such an arrangement, pilots need to consider that when they move to the right seat they've entered bizzaro world. Without some training and experience in right seat flying, specifically landings, you've significantly increased the risk of something bad (read expensive) happening. If you've ever thought about getting instruction in right seat flying, here are some of the challenges in store for you and a few suggestions on how to cope with them.

Understand the Limits

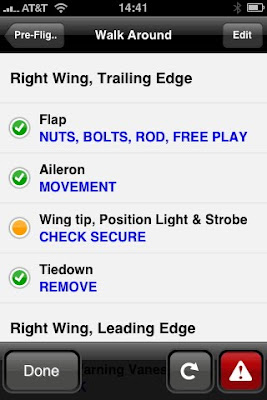

Though most GA aircraft have dual flight controls, they are certificated for, and primarily set-up for the pilot-in-command occupying the left seat. With the lion's share of the flight instruments positioned for the left seat, the pilot in the right seat can feel left out. The altimeter, airspeed indicator, and turn coordinator can be mighty hard to see. Even if you can see the instruments, there's the problem of parallax: You aren't looking straight at the instrument so you have to learn to judge what a needle is indicating or when the ball in the slip indicator is centered. And you can forget the attitude indicator in many aircraft. Instructors in the right seat usually learn to visualize bank angles and use outside references for estimating pitch.

The ignition key or magneto switches and virtually all other switches may be beyond your normal reach when you're sitting right seat and a clear view of these switches is often not available. The left yoke may be in the way or the left seat pilot's hands or arms may block your view. The throttle quadrant often blocks the right seat pilot's view of the landing gear lever and the gear position indicator lights. About the only things you may have close at hand from the right seat are the circuit breakers, flap switch and cabin heat controls.

When sitting right seat, you're going to be operating the throttle, prop, and mixture controls with your left hand. Virtually every pilot finds this arrangement awkward at first. You may even experience the thrill of leaning the mixture when you meant to retard the throttle, though most pilots rarely make this mistake more than once! I've even seen a few pilots grab the correct control, but in a fit of confusion, move that control the wrong way - advancing the throttle when they meant to retard the throttle.

The best radio push-to-talk (PTT) switch set-up for the right seat is to have the switch located on the right horn of the right seat control yoke. This makes sense because the right-seat flyer needs to have their left hand free for adjusting the throttle, prop, mixture or to set the radios and GPS. So naturally many aircraft manufacturers put the right seat PTT switch on the left horn of the control yoke. This means the pilot must momentarily switch hands or reach across their body with the opposite hand anytime they need to talk to ATC. One plane I occasionally instruct in has the right seat PTT switch mounted on the far right edge of the instrument panel, which can make for some interesting contortions.

Aircraft insurance policies and flying club rules often specify that all flying is to be done from the left seat unless the pilot holds a current flight instructor certificate or has specific authorization. Some aircraft have equipment limitations, like the often overlooked limit on the KAP 140 autopilot that a pilot must occupy the left seat when the autopilot is engaged. With all these limitations in mind, it's clear that flying from the right seat is not as simple as sliding over.

Illusive Landings

For most pilots, the biggest challenge with right seat flying is landing the aircraft. I've lost count of the number of pilots I've trained to fly right seat, but most have been flight instructor candidates. A few have been private pilots who simply wanted to see what it was like to fly from the other seat. I've known several instructors who became so comfortable flying right seat that they actually avoided ever flying from the left seat, even when flying solo. Switching back and forth can be a humbling experience, but flight instructors should be flexible and practiced in flying from either seat. If you aren't an instructor and you don't get much practice in the right seat, factor that into your personal minima and currency requirements. Like most anything else in life, right seat flying is a skill that must be practiced to be maintained.

The majority of learning right seat landing problems are difficulty aligning the longitudinal axis (yaw) and maintaining centerline alignment during the landing flare. Pilots who are new to the right seat frequently apply too much right rudder during the flare and the result is side loading on the landing gear at touchdown. The most effective teaching technique seems to be briefing the pilot on the common errors and solutions, then coaching them with real-time feedback about their rudder input. After 5 to 10 hours of practice, most pilots find right seat landings start to improve.

Double Vision

Ocular dominance, in my experience, plays an important role in a pilot's ability to maintain centerline and longitudinal alignment during the first few hours of landing from the right seat. For most people, their dominant eye is the same as their dominant hand: Right handed people tend to right eyed and left handed people are left eyed. Here's a simple test to determine your dominate eye:

With one of your arms extended and with both eyes open, align your thumb with some object that is more than 20 feet (6 meters) away. Close your left eye and if you see the object appears to remain aligned with your thumb, then your right eye is dominant. If the object no longer appears aligned with your right eye closed, your left eye is dominant.

I've taught right seat flying to at least three pilots who were right-handed, but who were left-eye dominant and these pilots seems to initially report more difficulty and feelings of awkwardness when transitioning to the right seat. Consider my unscientific representations of how ocular dominance might affect one's perspective from the cockpit. These photos have been exaggerated for effect, but illustrate the idea that significant re-learning is required when transitioning to the right seat. Pilots are often encouraged to look at the end of the runway during the landing flare and I suspect the reason this technique helps is because it reduces the parallax introduced by ocular dominance.

|

| Left Seat, Left Eye Dominant |

|

| Left Seat, Right Eye Dominant |

|

| Right Seat, Left Eye Dominant |

|

| Right Seat, Right Eye Dominant |

Right-Brain, Left-Brain

There are popular beliefs about right or left brain dominance, also known as brain function lateralization. The usual claims are that right-brain people tend perceive and think in a more global, holistic, and creative manner. Left-brain dominance purportedly helps one excel at procedures and rational thought. There are numerous on-line tests you can take that claim to tell you whether you are left- or right-brain dominant, though I'm not sure how much use this knowledge will be if you decide to try flying from the right seat.

Barring physical injury or disease, we each use of both halves of our brains every day. While parts of the right hemisphere provide motor control to the left side of the body and vice-versa, aside from obvious processes like speech (which is usually localized in the left temporal lobe for right-handed individuals and somewhat distributed between the left and right temporal lobes for left-handed people), there isn't always a clear pattern of specialization between brain hemispheres for global thought processes. It does seem safe to say that learning to fly from the right seat will require you to use your brain in ways you normally wouldn't, that's why it's difficult, and it's probably a good thing.

The key to safe and successful right seat flying is to get training from an authorized instructor familiar with aircraft you'll be using. Remember that when you reach for a control or switch using either hand, focus on your intention, not on how awkward it may feel. Expect to become fatigued more easily during your first few hours of right seat flying for the simple reason you'll have to concentrate on things you'd normally do unconsciously. Exercising your brain by thinking and coordinating in a different way can be challenging. Don't be surprised if you feel a bit like a student pilot at first, but don't worry. Right seat flying gets easier with practice.

+copy.jpg)