At the end of any trip comes the inevitable realizations about lessons learned as well as the comparisons and contrasts. Before I get to that, I'd like to ask readers who find my blog useful to consider making a donation to support my continued efforts. Over the last two-plus years, I've been writing regular blog entries that I hope are informative, useful, and entertaining. Writing takes time and, well,

time is money.

The amount you choose to donate is up to you and donating is easy: Use the PayPal donate button on the upper right side, though if you are using a blog reader that button might not appear. Just visit

the blog directly and you'll see it. Click the PayPal button and you can securely use any credit card or your PayPal account, if you have one. To those who have contributed in the past, thank you for continuing to support my efforts.

After 4 weeks "on the road," here are my observations about radio work, position reporting, paperwork, fueling, immigration/customs, weather briefings, airport security, and GA flying versus airline flying.

Aviation PhraseologyPurists insist that rules about communication need to be followed, and to a degree they are correct. I consider myself to be a bit of a purist, by the way. Rules and accepted phrases are intended to allow pilots and controllers to communicate efficiently and prevent mistakes, but rules can't cover every situation. In spite of efforts to standardize what is said on the radio, there will be local variations and spur of the moment improvisations because rules can't cover everything. For pilots who intend to travel to the Caribbean, here are my suggestions for radio communications.

If you don't understand what a controller has said because of their accent or phraseology,

don't delay responding while you try to puzzle out what they said. Instead, promptly reply with something like "I'm sorry, could you say again please, slowly ..." If you think you know what has been communicated, but are not sure, then by all means paraphrase what you have heard and don't fret too much about phraseology. Remember that the goal is communication - the exchange of meaningful information - not a stylized dance.

If you are a U.S. pilot, get used to including November in your callsign. The usual practice in the U.S. is to

omit the November part of your callsign when you include your aircraft manufacturer or model. Outside the U.S.,

the November prefix needs to be included. You may find the habit of omitting November to be as tough to break as I did.

There often will be no radar service in the areas in which you have choosen to fly, so brush up on position reporting. A abbreviated position report format is PTA-Next, which stands for:

Position (name of the fix)

Time (in Zulu)

Altitude (or flight level)

Next fix and your estimate for reaching that fix.

This is especially useful when handed off from one ATC facility to another, for example:

Raizet approach, November 1234 Delta, MEDUS, level niner zero, 1933 Zulu, estimating TASAR at 1950 Zulu

Approaching a terminal area that has no radar, expect to be asked to report your position relative to a VOR or NDB:

Say your distance and radial from Alpha November Uniform VOR

You can preempt this request by offering it when you check in:

V.C. Bird approach, November 1234 Delta, level niner zero, 25 miles out, ANU 192 radial, information Foxtrot

During pre-flight planning and while en route, pay particular attention to

FIR (flight information region) boundaries. They are depicted on Jepp and FAA IFR low altitude en route charts as well as on World Aeronautical charts. You can be prepared to provide an estimate to the FIR boundary by including the fix that falls on the boundary in your GPS flight plan, if you are GPS equipped.

You will probably be asked to "Report your estimate crossing the boundary" or "Report crossing the boundary," which mean when you think you'll cross the FIR boundary or when you are actually crossing it, respectively. Below is an excerpt from the Caribbean Low Altitude En Route Chart and you can see the blue dotted line representing FIR boundary around the Turks and Caicos. I've circled MICAS, a waypoint you might enter into your GPS flight plan if you were inbound on the airway A555.

Here are a few phrases that I got used to hearing and their U.S. equivalent:

"November 34 Delta, you are radar identified" = Radar contact.

"Say your leaving level" = Say altitude or flight level you are descending through.

"Say your passing level" = Say altitude or flight level you are climbing through.

"Backtrack runway zero seven" = Backtaxi on runway seven.

"November 34 Delta, copy ATC clearance." = IFR clearance available, advise ready to copy (Be prepared to do this while taxiing).

"I'll call you back" = Standby

Paperwork, Flight Plans, CustomsBecome familiar with ICAO flight plan forms. They aren't difficult, they're just different. Both

DUAT and

DUATS offer HTML version of these that you can experiment with, but remember that flight plans originating outside the U.S. and its territories will need to be filed with the local ATC authority. This means you'll have to use the

paper version and fax it or hand-carry it to the appropriate office.

Below is an excerpt of a DUAT ICAO flight plan form. When you specify your aircraft's equipment, start with S (for standard) and then include every other type of capability your aircraft has. The Duchess I was flying was GPS equipped with two VOR receivers, two glideslope receivers, and DME so the acronym I came up with was SD GLO. The RMK section is where you can enter remarks and I always put ADCUS, which is supposed to indicate to ATC that they should "advise customs" at your destination on your behalf prior to your arrival. Prior notification of customs is a requirement for all countries.

The part of the ICAO flight plan that references dinghy is referring to what you might know as a life raft. You'll need to put the number of life rafts, the number of people the rafts can hold, whether or not they are covered, their color, and the survival equipment it includes. Next comes emergency radio equipment, survival equipment and life jackets.

When flying in the Caribbean you are required to carry a life raft and one life jacket for each occupant. Most commercial life raft you can purchase come with a survival kit that includes signal flares and other equipment. I strongly recommend that you also have a hand-held, waterproof VHF transceiver and a 406 Mhz GPS personal emergency locator beacon. Lastly, enter your fuel endurance in hours and minutes.

Learn about General Declarations or gendecs. You can download a PDF version

here. Here's an example of how you might fill one out. Be sure you have

at least four copies of your inbound gendec when arriving and four copies of your outbound when departing.

Customs Handling

Customs Handling

Though it can be costly, you can save a lot of time and hassle by contracting with a handling service if your destination is at a large airport. The handler will expedite the processing of your gendecs, get you through immigration/customs, direct you to where you pay landing and departure fees, and arrange re-fueling. Handling service charges range from $100US to as much as $250US and you can usually find the appropriate phone numbers in the

Bahamas and Caribbean Pilot's Guide.

There is generally less hassle and less waiting at smaller airports of entry where you may be able to figure out your own handling without much trouble.

Landing fees and taxes are usually not payable with a credit card. Some offices accept the EC (Eastern Caribbean dollar), others want Euros or U.S. dollars, so call ahead or just always have plenty of cash with you. Larger airports usually have ATMs that may allow you to obtain the local currency.

Fuel

Fuel can be very expensive and at many smaller airports, 100 low-lead aviation gasoline

is often not available. Again, check the excellent

Bahamas and Caribbean Pilot's Guide for phone numbers and details.

Where fuel is available, credit cards may not be accepted and you may have to pay in cash. U.S. dollars seem to be preferred or, in some cases, required. Phone ahead to be sure fuel is available and to learn of the payment methods accepted.

I recommend supervising the re-fueling process. Afterward, always check the fuel quality carefully. I found traces of water and debris after being refueled in a couple of places. I recommend the GAT jar for sumping fuel because you can easily drain a substantial amount for a more thorough inspection.

Weather Briefing and ThunderstormsDetailed weather data can be hard to come by in many parts of the Caribbean. METARs and TAFs (airport weather observations and forecasts) can be had through a variety of sources, but the forecasts can be annoyingly vague. Pilot reports and winds aloft forecast seem to be rare or non-existant. Here's what a DUAT output looked like for part of my trip. Not much information, is it?

Nexrad images are available for

Puerto Rico, but other than the long range base reflectivity product there are no other weather radar products that I could find. Various

satellite images are available and there is a

high level prog chart that gives you an overall idea for the Caribbean weather patterns.

Many airports do not broadcast any surface weather conditions over the radio, but some do so over the voice portion of a VOR. The tower (if there is one) will provide you with the conditions, otherwise you are on your own.

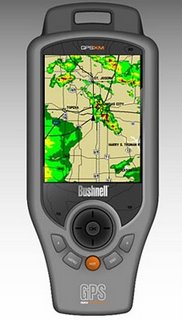

I found most thunderstorms to be isolated and easy to see and avoid, but embedded thunderstorms are possible. The XM weather feature on our hand-held Garmin 496 quit working after we left Providenciales and didn't work again until we returned to the U.S. mainland. Pilots of GA aircraft without on-board radar need to weigh their options and risks carefully. If you don't have radar or a strike finder and you can't stay in visual conditions while you maneuver around build-ups, you probably shouldn't be flying. Flying early in the morning can help you avoid most thunderstorms. If you're faced with an approaching thunderstorm, delaying your departure by only a few hours or a day may be all that's needed to substantially reduce your risk.

Get used to writing down two altimeter settings and taking note of the transition altitude for the area in which you are flying. You'll use

QNH when you're below the transition altitude. Above the transition altitude you'll refer to your altitude as a flight level (or just level) and set

QFE on your altimeter. Some ATC facilities see that you are a U.S. registered aircraft and provide the altimeter settings in inches of mercury as a courtesy, but don't count on it. Some altimeters display millibars and inches of mercury in separate Kollsman windows and you can set the G1000 preferences to millibars. Otherwise, you should have a

millibars to inches conversion table handy.

Airport SecurityI don't recall seeing armed police presence at any of the Caribbean airports I visited, save the ones in U.S. territories. Another difference between U.S. CBP and immigration/customs in Caribbean countries is the manner in which you are treated. In Caribbean countries, the authorities may search your bags, examine your travel documents, and ask you questions about your travel plans, but the people doing this are not armed and only once (in Trinidad) did I feel there might be a presumption that I was guilty until proven innocent. The U.S. TSA posts signs promising to treat you with dignity and concern, but the very fact they have to post such a sign seems intended to prepare you for just the opposite. In the countries to which I traveled, I was generally treated with respect by people who felt no need to post a sign saying that this would be the case.

Outside the U.S., pilots are referred to as "captain," a title of respect that recognizes you are in command of an aircraft. I felt U.S. Customs and Border Protection and TSA officers simply saw me as a potential threat. When they determined that I wasn't, they just dismissed me and went on to the next potential "target." Be prepared for culture shock if you re-enter the U.S. or one if its territories after spending a bunch of time in other parts of the Caribbean.

My comments and opinions are based on my firsthand experiences and it is not my intent to stir patriotic fervor or righteous indignation in my U.S. readers. If you don't like what I've said here, by all means feel free to disagree. Remember that the U.S. is (or at least was) based on the freedom to dissent, not the requirement to conform to one accepted viewpoint.

Flying Yourself versus The Airlines

Piloting an aircraft through Caribbean airspace will take longer and cost more than being transported in an airliner, but the GA route is a heck of a lot more fun and, in some cases, substantially faster.

Take our return flight from V.C. Bird airport in Antigua to San Juan, Puerto Rico on American Airlines. We arrived at 1pm for a 3:05 departure. We allowed plenty of time to get through the lines for departure tax (yes, there's a tax even for airline passengers), immigration, and security. Then we waited about an hour and a half before they began boarding the aircraft.

Near as I can tell from the cabin announcement, the 757's APU was deferred (inoperative) and we required an "air cart" (a supply of high pressure air) to start the first engine. Getting the air cart took about 30 minutes and while we waited on the ramp in the blazing sun and high humidity, we essentially had no air conditioning. The cabin crew was great. They opened a couple of doors for better ventilation and the flight crew did their best to keep us up-to-date on what was happening.

Once the air cart arrived and the engines were finally started, we had air conditioning and there was more bad news. We were already over 45 minutes late for our departure when the captain informed us there would be an indeterminate delay: The tower had informed them "something was on the runway." No one knew exactly what was on the runway, but we sat and waited, and waited, and waited. After nearly two hours of waiting on the ramp, we finally made our way to the runway for takeoff. During this time, the cabin crew handed out ice water, even though no refreshments were scheduled for what should have been a short 45 minute flight.

We never found out what was on the runway or why it took so long to clear, but I have a theory. I had landed on the same runway the day before and had noticed that two large, parallel strips of pavement at the threshold had recently been surfaced. On the landing rollout the previous evening, I could smell the fresh asphalt and oil. In addition, there was no white center line stripe for the first 900 feet or so. My theory, and it's just that, was some of that fresh pavement buckled or otherwise deteriorated. This is a plausable theory since a Virgin Atlantic 747 and some other pretty big aircraft had arrived earlier in the day. When we took the runway for takeoff, I noticed that a new white stripe had been painted since I landed the evening before.

We finally arrived at San Juan a little past 7pm, over 3 hours late. On the way, there was a loud, troubling, low-frequency buzz coming from the left engine. It changed with the power settings and was very pronounced at takeoff and climb thrust, but diminished at cruise and went away almost entirely during descent. Departing the aircraft after landing, I passed the head flight attendant and mentioned "I hope the flight crew knows about that nasty low-frequency vibration on the number one engine." He gave me a sort of dismissive smile and said "I'm sure they do, sir, I'm sure they do."

Had we flown the Duchess to San Juan, we could have arrived at the airport at noon and it is very likely that by 1pm, we would have finished the preflight, had our gendec paperwork, and our flight plan filed. The flight to San Juan would have taken about 1 hour and 45 minutes - arriving at approximately 2:45pm. After landing, clearing immigration, customs, and paying our landing fees would have taken about 45 minutes, putting us curbside at about 3:30pm which would have been 25 minutes past the scheduled

departure time of our airline flight. The Duchess would have arrived nearly an hour earlier that the scheduled airline arrival at San Juan or more than 4 hours before our delayed arrival.

But you ask, how could the Duchess have departed if there was something on the runway? Well it turns out the tower was allowing intersection departures on the runway, but the takeoff distance remaining was too short for a 757. So the Duchess could have beat the airlines handily, albeit at a higher cost. Of course the airlines have more sophisticated equipment that would have made the flight safer had the weather been bad.

There ends my Caribbean Conclusions. I hope my little travelogue has been informative, interesting, and that it may encourage other U.S. pilots to explore the Caribbean themselves.

+copy.jpg)