On October 19, 2004, about 1937 central daylight time, Corporate Airlines (doing business as American Connection) flight 5966, a BAE Systems BAE-J3201, N875JX, struck trees on final approach and crashed short of runway 36 at Kirksville Regional Airport (IRK), Kirksville, Missouri. The flight was operating under the provisions of 14 Code of Federal Regulations Part 121 as a scheduled passenger flight from Lambert-St. Louis International Airport, in St. Louis, Missouri, to IRK. The captain, first officer, and 11 of the 13 passengers were fatally injured, and 2 passengers received serious injuries. The airplane was destroyed by impact and a postimpact fire. Night instrument meteorological conditions (IMC) prevailed at the time of the accident, and the flight operated on an instrument flight rules flight plan.

Instrument approach procedures all have the same goal: Safely direct the aircraft out of the clouds and into visual conditions so the pilot can land, while not allowing the aircraft to get too close to solid objects. You definitely don't want to run into anything while you're in the clouds, but it's still possible to run into obstructions even after you've reached visual conditions if the visibility is bad or it's night time.

There are two broad categories of instrument approach procedures (or IAPs): Precision and non-precision. The main difference between these categories is that precision approaches provide the pilot(s) with vertical descent guidance to a decision height (altitude above ground level) at a point very close to the runway. Non-precision approaches require the pilot(s) to determine their current position relative to the runway and descend to specific altitudes based on that position. There may be several step-down fixes in a non-precision approach before the pilot(s) can descend to the minimum descent altitude (MDA). Once at the MDA, the pilot(s) are not allowed to descend any lower until the required visual cues defined in 14 CFR 91.175 are present. Flown properly, all instrument approaches should provide adequate obstruction clearance, but precision approaches are statistically 5 times safer than non-precision approaches.

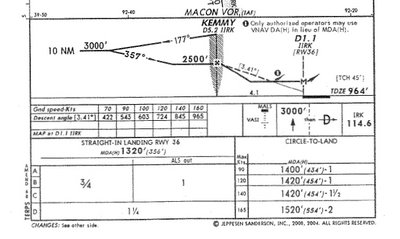

There are two schools of thought about how to descend to the MDA when flying a non-precision instrument approach procedure. One way is, once you have reached the point where you can descend to the MDA, to do so as quickly as possible in hopes of visually acquiring the runway environment early. The other school of thought is to fly a stabilized descent that will get you to the MDA a mile or so before the missed approach point. The crew of Flight 5966 descended at a rate of 1200 feet per minute and here's what the descent profile looked like.

Note that even with a ground speed of 160 knots, the approach chart shows a recommended descent speed of just 965 feet per minute.

I'm not a big fan of teaching instrument students to dive for the MDA and the argument that an aggressive descent might get you into visual conditions seems to have a hollow ring. I'd need to be pretty motivated (have some sort of emergency or urgent situation) to pin all my hopes on a non-precision approach with very low visibility or cloud ceiling. Fly a stabilized descent, reach the MDA a mile or so prior to the missed approach point. If you don't see anything, fly the missed approach procedure and go to your alternate or try to find a precision approach nearby.

When descending on a non-precision approach, I don't want to descend so slowly that I don't get down in time to have a chance of reaching visual conditions and landing. This is where the Jeppesen approach charts have an advantage - they list the recommended descent rate while the FAA charts require you to look up the descent rate in a separate table. If the descent angle is a standard 3˚, you can approximate a stabilized descent rate by multiplying your groundspeed in knots by 5. For example, a ground speed of 110 knots would require a 550 foot per minute descent rate for a 3˚ descent.

My rule is to never let the vertical descent rate in feet per minute be greater than the aircraft's height in feet above the ground. AC 120-71A Standard Operating Procedures for Flight Deck Crewmembers also recommends a maximum descent rate of 1000 feet per minute when at or below 1000 feet AGL. If I'm descending from 2500 feet to 500 feet above ground level (AGL), I may start with a descent rate of 750 or 1000 feet per minute. Once I pass 1000 feet AGL, an unarrested descent rate of 1000 feet per minute gives me just 1 minute before I would hit the ground. At 1000' AGL I'd start slowing the vertical descent rate. I've found that uttering the phrase "A minute to live" works wonders with instrument students who tend to descend aggressively. For GA pilots operating under Part 91, I recommend choosing a stabilized descent rate and maintaining a consistent airspeed or, if you have DME or GPS, a consistent ground speed.

Someday there will be precision approaches everywhere. Until then, make sure you give yourself more than a minute to live when descending inside the final approach fix on a non-precision instrument approach.